Follow the bottle towards less waste

The simplest way to reduce waste is to produce less. You may have heard this phrase already. It is the reason why we consider how we carry out different tasks rather carefully all the way through from the vineyards and up to the final bottle. We invite you to join in the journey. The first stop is the bottle at your hand.

The champagne bottle

The classic curvy bottle of the Champagne-region is called la Champenoise. It is colored green mostly, it contains 0,75 liters, and it is not that many years ago it succeeded with the dream of many getting rid of some body weight (picture 1). Currently the bottle weighs 835 grams instead of 900, which is 7% less. This means that we can fit more into a transport pallet.

The bottle itself can be used only once. It has got to be robust enough to stand the powerful pressure of six bars inside the bottle. This explains why the glass - even lighter than before - must be more vigorous than a bottle made for ordinary still wine.

When you scrap the bottle, the glass will be recycled like any other kind of glass, obviously.

Foil and label

A multitude of rituals follow, once you get ready to open your bottle. You look for the almost invisible spot where you can open the foil easily. Then you move on to unwind the wire cage. Now you are set to pop your champagne.

When we design our foils and labels, we use the highest standard available at the manufacturer when it comes to sustainability.

This means that the foil is made of a kind of polyethylene – plastic – that has been made from cane sugar. It can be recycled 100%.

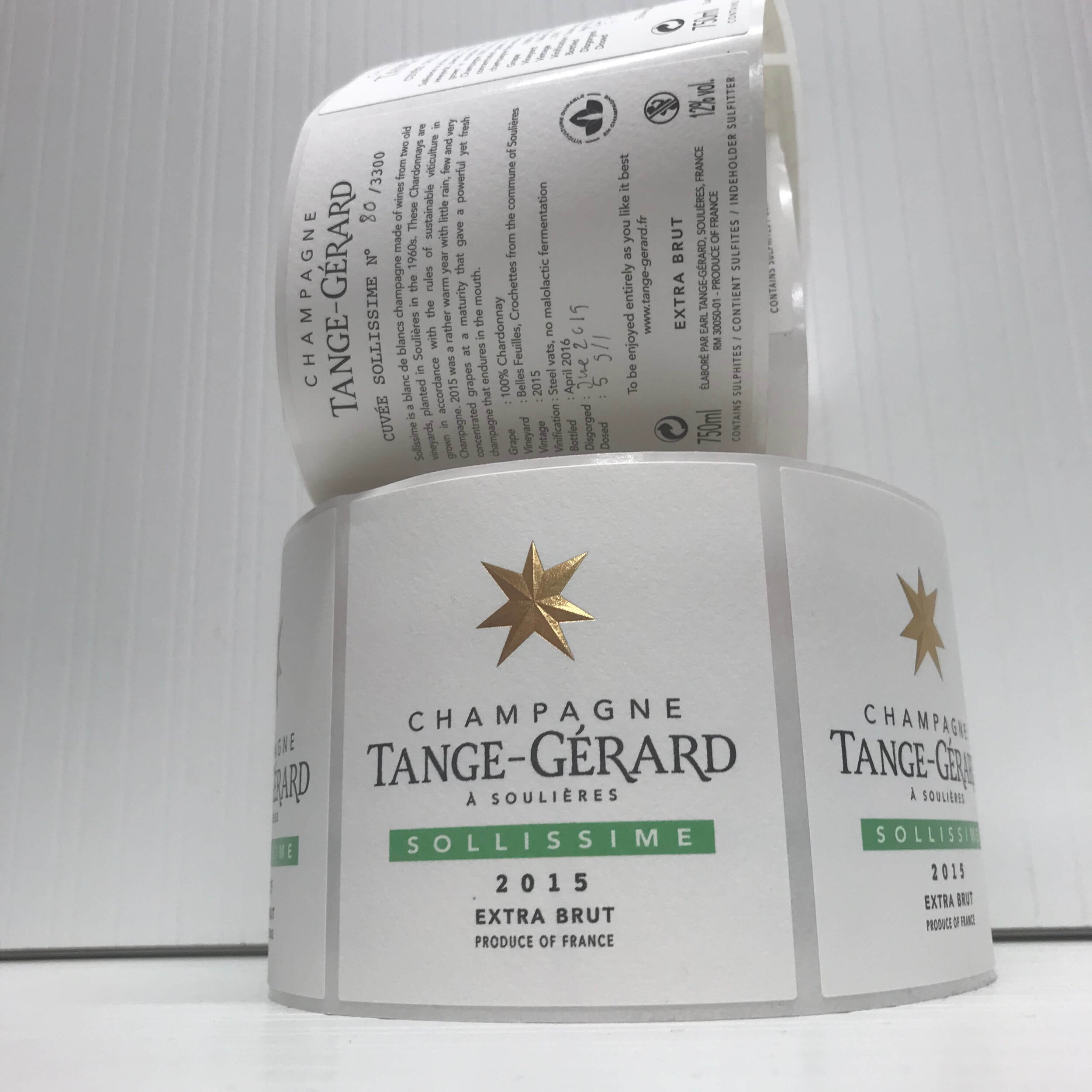

The labels are printed with water-soluble ink. They are made from cotton fibers (picture 2).

Currently we receive the labels as stickers. They sit on a material, that is not recyclable because it contains plastic. A better solution, which will involve that we return the plasticized material once we have used the stickers, is being tested currently.

The tops and corks

The champagne bottles are closed with corks, constituted by granulate. These tiny pieces of real cork are treated with CO2 to minimize the risk of the TCA chemical that can cause corked wine (picture 3). Once treated, the pieces are put together with glue, approved for food.

Since 2021, the manufacturer takes back the corks to recycle them as insulation panels. We collect our own corks to pass them on, and we may take yours as well if you get them to us.

On top of the cork sits the wire cage with the capsule, that are both reusable. But maybe you are amongst those of us who keep the tops of your special champagne bottles? Souvenirs, souvenirs…

Well, we do ourselves, not for memory reasons though. We are not collectors. But so many others are, and we regularly receive mails from these placomusophiles to ask for tops. So, we keep the capsules from empty bottles so that we can pass them on in the envelopes with stamps that we receive for the purpose. We normally do not give labels as they are not secondhand. Now you know.

“We know that smashing boxes and paperboards contribute to provide both color and shape to the champagne dream.”

Why we skip some packaging

The magical wrapping and packaging stage the myth about the perfect champagne moment. Well, not with us.

We know that smashing boxes and paperboards contribute to provide both color and shape to the champagne dream. It simply looks much better when you offer champagne.

The problem is that these boxes sooner or later will end up in your bin. Let us also mention glossy brochures while we are at it. 33% of CO2 emissions in the champagne profession were due to packaging in 2015. That is the reason why we decided to skip it from the beginning in 2009.

However, we want to suggest at bit on top of the naked bottle, and therefore we have designed fact sheets that you will find in our webpage to print as you need them.

The journey continues. Please join us in the vineyards at wintertime to learn how we manage the yields.

Branches in the vineyards

During winter we cut off most of the branches from last year to manage the future yields and the vigor of the plant. Then we spread them evenly through the plot.

In one of the cold days of winter when the upper part of the soils is frozen, we send a tractor through the plot. This machine is equipped with tools that can crush the branches and turn them into wooden chips (picture 1).

They contribute to our maintenance of the mulch layer of the upper soils, that otherwise disappears with time due to erosion and wind.

Some of the older, thicker branches are burnt in the fields to provide minerals and the rest is kept in a corner at the domaine as they do an excellent job as charcoals for barbecues in the summer.

It is during the pruning season as well, that the tendrils of the vines are more visible than at any other time of the year, because the leaves are gone. We cut off the prettier ones to use them for different decorative purposes (picture 4).

When the grapes are too many

The grape harvest at the end of summer provides us many tons of grapes (picture 2). We make champagne from a certain number of kilos per hectare. Champaghe houses and wine growers, buyers and sellers of grapes agree on this quota every year.

We try to hit this amount rather closely every year. Partly because Alain Gérard when needed will remove some clusters at a young stage during summer.

Some extra grapes are fine

We manage our expected yields when we prune the vines in the winter. Still a little surplus in summer is not too bad. Problems that may cost us some grapes are plentiful: disease, pests, bad weather. This partly explains why the final number of grapes can vary greatly between the years.

If we end up with a surplus, we still pick all mature grapes and press and vinify them. We keep those that we like best to make champagnes. What exceeds the quota will be sold for distillation in a company, specialized in this kind of production.

Back in our vineyards the second generation of grapes have matured. It is much smaller than the first when it comes to quantity and not of the same quality. Therefore, these late grapes are mainly used for a few clafoutis for those who can stand the seeds of grapes for wine. What will finally be left in the vineyards, is highly appreciated by the birds.

We continue the journey by moving into the processes of the vinification.

In the winery

The production of wine and champagne takes place in the winery and then in the cave.

In Champagne, we press the grapes with their stems. 5.100 liters of must can be extracted from 8.000 kilos of grapes. After the pressing, a compact mass of stems, skins and seeds lie behind in the press together with must that is still in the berries. This pile of grape leftovers - the aigne - is extremely acid (low pH). It goes for distillation, and eventually, what will be left can be used by farmers.

The extreme acidity of this mass makes it a possible way to change the pH value in the chalky and therefore rather alkaline farmland of Champagne. A pH that is too high may block the absorption of important nutrients like boron, magnesium, iron, copper, and zinc. A light treatment with an acidity bomb like the aignes is a biological and even local treatment that works.

Champagne is a sparkling wine, and the capacity to form bubbles is created when we ferment the wine twice.

The grapes will arrive from one or several plots. We press them to obtain the must, that is fermented into a still wine, that we mix crisscross plots, grape varieties, and years, before we bottle the blend on the final champagne bottle where it will complete the second alcoholic fermentation.

Clean wastewater

Impressive amounts of water will be used during the grape harvest.

A top hygiene is crucial to make the best possible wine and avoid fungus and unfortunate bacteria. Therefore, absolutely everything: presses, tanks, floors, walls with tiles, are washed down several times every day (pictures 1 and 2).

Since the early 1990’s the law has required, that these many liters of water must be purified to avoid washing out big amounts of organic material from the pressing. Today, all wine presses in Champagne are equipped with installations to clean the wastewater before it is conducted further on. Already in 2012, more than 98% of the wastewater was purified according to Comité Champagne.

“A top hygiene is crucial to avoid problems. Therefore presses, tanks, floors, walls with tiles are washed down sevel times every day.”

The lees from the tanks

The freshly pressed must ends up in open vats under the presses. From here, the must will be transferred into the steel vats where the first alcoholic fermentation will take place. Typically, this process endures 10-14 days. Once the sugar has changed into alcohol, the young wine will be transferred to another vat.

Every time the wine changes its whereabouts, some sediments will stay behind at the bottom of the vat. This mix of dead yeast, leftovers of seeds, pulp and tartar is called lees. It serves as a by-product from the vinification. After the required distillation elsewhere, the different elements will be separated and dehydrated and eventually serve in industries like pharmaceutics, skincare, and the food industry.

During the first spring after the grape harvest, the wine will be bottled at the final champagne bottle (the tirage). Quite some packaging is involved. The empty bottles arrive on wooden pallets wrapped in plastic. Capsules and small plastic-recipients (bidules) are packed in boxes. All this wrapping and packing is sent back to the supplier afterwards.

Lees from the disgorgement

The young wine is transferred with sugar and yeast to the final bottle. As soon as it is closed with its temporary capsule, it will be stored in the cave for the second alcoholic fermentation to begin. The bottle will not be out anytime soon. Typically, we keep them in the cave between 4 and 10 years, depending on the type of champagne.

During the second fermentation, another batch of lees has developed. Inside the bottle, the yeast has eaten the sugar. Once the meal is finished, the yeast cells cannot survive long in the closed bottle. They sediment inside the bottle, and this layer of lees will be collected in the bidule behind the capsule during the process of remuage in the weeks before the disgorgement.

As the capsule is removed during disgorgement, the internal pressure inside the bottle, will let the opened capsule and bidule with its contents of lees go off (picture 4). They are all collected in a container and subsequently cleaned to separate the lees that goes for distillation and the rest is sent to a company specialized in recycling of capsules and recipients.

The bottle will only be closed with the final cork at this point when the champagne is completely limpid. It is also the moment of adjusting the sweetness of the final taste with the dosage.

From this stage, we will bring the bottles to sell within the next year from the cave.

Getting ready to go

However, the bottles rest some months further before we dress them up with their foils and labels. We want to be very sure that the dosage from the disgorgement has integrated well in the champagne.

The bottles are placed in carton boxes, that are strong enough to travel on a pallet. It remains a heavy experience for bottles at the bottom. Otherwise, we have opted out from uniquely looking packaging with creative design details, because they tend to have a cost when it comes to CO2 emissions.

This is the journey of by-products and waste as we look at the creation of a bottle of champagne, from the vineyards and until the final bottle.

Since we obtained our first certification in 2016 (Viticulture Durable en Champagne), we have noticed that the methods take us in the same direction in our private lives. Anything else does not really make sense any longer. As work and spare time do not have very distinct delimitations in a life like ours, we invite you for a quick look into it

“The methods take us in the same direction in our private lives. Anything else does not really make sense.”

In the house

The house and its buildings in Soulieres are the center of our work life. Like you probably and so many others, we found ourselves in containment during the covid-19 pandemic in the spring 2020. We decided to move our family life to the village in that special period. And this has been a change that seems to endure.

The house itself and the buildings around were stuffed from basement and up to the roof with all sorts of belongings, that did not interest anyone for decades. We began to clear up the mess.

We chose that everything of some value ought to be put back in business as our starting point. Therefore, we sorted, repaired, passed on or recycled our findings. We decided to not discard something usable and not to buy something that is available in the house. Even the style or color may not be what we would have chosen ourselves.

To recycle and to compost

Some examples: The metal posts from the espaliers in the vineyards rust, and so we change them now and then. However with a bit manual welding (picture 1), they can be recycled to protect young vines against being damaged by the ploughing tools.

During the confinement time, we spent some of the time saved in transport to lay out a vegetable garden. The closed garden was extended into the pasture behind the house to plant an orchard. This area was never cultivated to our knowledge, and we had to remove a lot of stones from it. They were put in use as support between the upper plots in Loisy-en-Brie and a small stream that carries water occasionally in spring (picture 3 in the top).

Finally, we have put retired wooden boxes, made to store bottles in the caves, in use (pictures 3 and 4) to grow tomatoes and other plants that may benefit from the warm temperatures of the courtyard during the growth season. When the boxes are too worn to store bottles in the caves, they still possess practical and aesthetic value for us

This altered focus can be measured directly on the volume of the garbage bin, the number of trips to the recycling collection place and the development of our compost in the garden. The dustbin used to be rather full every week, now down to around 20% on average. The trips to the recycling place have slowed down as well, and finally the compost has become a habit. It was emptied for the first time this spring.

We have a strong feeling that the real journey is only beginning. Such a thrill.